The global annual average temperature is set to reach a new record high soon, influenced by quickly rising ocean surface temperatures and the start of an El Niño event. The current warmest year, 2016, is already well behind us. Yet, the following years all established themselves in the top 8 of warmest years on record (WMO, 2023). In this article, we discuss the continuation of global warming, the likelihood of a new record warm year in the upcoming years, and the impact of sea surface temperatures and the onset of El Niño on this trend.

During the super El Niño of 2015/2016, the global annual average temperature reached the highest value on record. This El Niño, amplifying the global warming signal, played a major role in the rapid warming of the globe and reaching this record high global temperature (Hu & Fedorov, 2017). The temperature reached 1.25°C above pre-industrial levels according to Copernicus, and 1.28°C according to the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). Note that according to Copernicus, 2020 tied this value, making both 2016 and 2020 the warmest years on record.

A few cooler years: no anthropogenic climate change?

Recently, deniers of anthropogenic climate change regularly use the stagnating or slightly decreasing annual global temperatures after 2016, presenting them as proof that global warming is no longer happening. The last 8 years are cherry-picked and magnified to show a decreasing trend; however, this claim is incorrect.

Climate variability

Besides the fact that a period of 8 years is a rather short timeframe to track down climatological trends, the deniers of antropogenic climate change are forgetting about a crucial aspect: climate variability. Natural variations, with causes that can range from volcanic activity and ocean currents to changes in solar radiation, lead to year to year variations in the weather and therefore slightly varying global average temperatures.

The impact of the ENSO (El Niño and La Niña) cycle

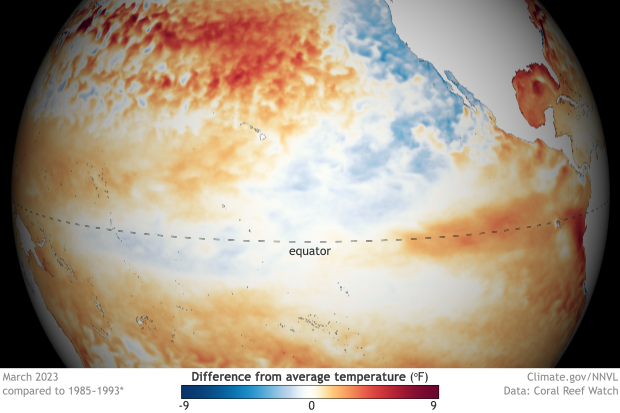

One of the most important sources of climate variability is the ENSO cycle. El Niño is a phase of ENSO characterized by warmer-than-normal sea surface temperatures in the central and eastern tropical Pacific. This is both caused by and leads to changes in atmospheric circulation patterns and thereby impacts weather and climate conditions globally. La Niña is the opposite phase of ENSO, characterized by below average sea surface temperatures in the same region.

This cycle of alternating El Niño and La Niña phases has a very large impact on the year-to-year climate variability on Earth (McPhaden et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2017). Specifically, El Niños generally lead to an increase in the average global temperature due to atmospheric heat release (Hu & Fedorov, 2017). Super El Niños even have the potential to (temporarily) increase the global annual temperature by as much as 0.2°C (Hansen et al., 2006).

Super El Niño and consequent La Niña behind observed ‘stagnation’ of global temperature

This way, the super El Niño of 2015/2016, along with human-induced global warming through greenhouse gas emissions, contributed to 2016 becoming the warmest year on record. The years after were, however, followed by a weak to moderate and rather long lasting La Niña phase of the ENSO cycle, temporarily causing a stagnating global temperature. In between, during 2018-2019, there was a short El Niño phase, however, this El Niño was rather weak, unlike the super El Niño of 2015-2016. Now La Niña has ended, the stagnation of the global temperature is likely to come to an end, too.

Research confirms year-to-year variability and global warming signal

Previous studies have already shown that global warming continues at a steady rate, when you isolate the warming trend from impacts that cause year-to-year variability.

For example, when researching the global temperature evolution from 1979-2010, Foster & Rahmstorf (2011) removed the impacts of known short-term temperature variations such as the ENSO cycle, volcanic aerosols and solar variability. Not only did this analysis confirm the strong influence of known factors such as ENSO on short-term variations in the global temperature, the global warming signal also becomes more evident as noise caused by the short-term variations is reduced (Foster & Rahmstorf, 2011). Not only do they conclude that the rate of global warming has been remarkably steady from 1979 through 2010; there is also no indication of any decelleration in global warming outside of the variability induced by aforemenetioned, isolated natural factors. Also, there was no acceleration in the isolated global warming trend found in this specific study either, for that matter.

El Niño expected to develop

According to the ENSO diagnostic discussion from the Climate Prediction Center, which is part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), there is a 62% chance of El Niño developing during May-July 2023. A significant warming along the South American coast has already been observed, generally an indication for the onset of El Niño. Additionally, there is a 40% chance of a strong El Niño developing toward the end of the year.

Global Sea Surface Temperatures already record high

Worryingly, preceding the likely establishment of an El Niño pattern, the global sea surface temperatures (SSTs) have already reached a record high level, more than 2 standard deviations above the 1982-2011 mean. The upcoming El Niño would most likely only amplify this warming.

A record warm year is looming

The atmospheric response generally lags behind the changes in sea surface temperature following El Niño (Kumar & Hoerling, 2003). More specifically, the impact on the atmospheric temperature commonly occurs a few months after the peak of an El Niño. It is therefore likely that if a (strong) El Niño forms this year, a new global average annual temperature record will be set in 2024 or 2025.

According to BBC news, Dr Josef Ludescher from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Research said that if a new El Niño follows on top of the recent, unprecedently high SSTs, an additional global warming of 0.2-0.25°C is likely. A warming of this magnitude could push the global temperature (temporarily) over 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, the lower target of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change.

This is also in line with a climate update issued by the WMO about a year ago, in which was mentioned that there is a 50% chance that the global average temperature will already temporarily exceed the 1.5°C limit in the upcoming 5 years (WMO, 2022). In this report was also stated that there is a 93% likelihood of at least one year between 2022-2026 becoming the warmest on record. If anything, the recent developments with regard to the ENSO cycle and the unprecedented sea surface temperatures will only make these outcomes more likely.

Signs of escalating heat

Even though a new global annual average temperature record hasn’t been set in recent years, the effects of global warming manifests in various ways. The record-high sea surface temperatures, for instance, indicate a significant shift in the Earth’s heat budget (von Schuckmann, 2023). Oceans store far more energy than the atmosphere, as water has a much larger heat capacity than air. A record-warm ocean thus implies the storage of a substantial amount of heat.

Moreover, many unprecedented temperature events have occurred worldwide this month alone. As a warming climate makes temperature extremes more likely, these records are in line with the climatological warming trends. Dozens of weather stations in North Africa and Southwestern Europe shattered their previous April warmth records, with some exceeding the previous records by a large margin. Astonishingly, Cordoba, Spain, broke its previous April record of 34.0°C by nearly 5 degrees, registering a maximum temperature of 38.8°C. Earlier this month, several Southeastern Asian countries also experienced all-time temperature records. These events are just a fraction of the numerous records broken this month alone.

The impending global temperature milestone

In conclusion, the evidence suggests that a new record high global temperature will be set in the near future. While recent years have not surpassed the record warmth of 2016, they still rank among the top 8 warmest years. With the likelihood of a new El Niño event and already emerging unprecedented sea surface temperatures, it’s not a question of if, but when in the upcoming years the warmest year on record will be measured. Additionally, a new record warm year may already push the global temperature beyond the 1.5°C threshold set in the Paris Agreement.

References:

Chen, L., Li, T., Wang, B. and Wang, L., 2017. Formation mechanism for 2015/16 super El Niño. Scientific reports, 7(1), pp.1-10. Link: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1038/s41598-017-02926-3.pdf

Foster, G. and Rahmstorf, S., 2011. Global temperature evolution 1979–2010. Environmental research letters, 6(4), p.044022. Link: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/6/4/044022/meta

Hansen, J., Sato, M., Ruedy, R., Lo, K., Lea, D.W. and Medina-Elizade, M., 2006. Global temperature change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103(39), pp.14288-14293. Link: https://www.pnas.org/doi/abs/10.1073/pnas.0606291103

Hu, S. and Fedorov, A.V., 2017. The extreme El Niño of 2015–2016 and the end of global warming hiatus. Geophysical Research Letters, 44(8), pp.3816-3824. Link: https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/2017GL072908

Kumar, A., & Hoerling, M. P. (2003). The nature and causes for the delayed atmospheric response to El Niño. Journal of Climate, 16(9), 1391-1403. Link: https://journals.ametsoc.org/view/journals/clim/16/9/1520-0442_2003_16_1391_tnacft_2.0.co_2.xml

McPhaden, M.J., Zebiak, S.E. and Glantz, M.H., 2006. ENSO as an integrating concept in earth science. science, 314(5806), pp.1740-1745. Link: https://www.science.org/doi/abs/10.1126/science.1132588

von Schuckmann, K., Minière, A., Gues, F., Cuesta-Valero, F.J., Kirchengast, G., Adusumilli, S., Straneo, F., Ablain, M., Allan, R.P., Barker, P.M. and Beltrami, H., 2023. Heat stored in the Earth system 1960–2020: Where does the energy go?. Earth System Science Data, 15(4), pp.1675-1709. Link: https://essd.copernicus.org/articles/15/1675/2023/

WMO (World Meteorological Organization). (2023, January 12). Eight warmest years on record witness upsurge in climate change impacts. Retrieved April 27, 2023., from https://public.wmo.int/en/media/press-release/past-eight-years-confirmed-be-eight-warmest-record

WMO (World Meteorological Organization). (2022, May 9). WMO Update: 50:50 chance of global temperature temporarily reaching 1.5°C threshold. Retrieved April 27, 2023., from https://public.wmo.int/en/media/press-release/wmo-update-5050-chance-of-global-temperature-temporarily-reaching-15%C2%B0c-threshold