The Hellmann number (H) is a cold index mainly used in The Netherlands and Germany. It is a measure of the cold occurring during the winter season and the months surrounding the winter season, to quantify the severity of a given winter. The Hellmann number is also referred to as ‘cold sum’ in English, ‘koudegetal’ in Dutch, or ‘Kältesumme’ in German. The Hellmann number is named after Gustav Johannes Georg Hellmann, a German meteorologist and climatologist who is the inventor of this cold index.

Computation of Hellmann Number

The Dutch Royal Met Office (KNMI) calculates the Hellmann number by adding up all the daily average temperatures from November 1st to March 31st that are below freezing (0°C). In this calculation, the negative signs are removed. This means that a daily average temperature of -2°C, yields a Hellmann number of 2.

Find an extended explanation of the Hellmann number on the website of the KNMI (in Dutch).

While the Hellmann number is traditionally calculated from November 1st to March 31st in The Netherlands and Germany, on this website, we extend the computation to cover the entire winter year, from July 1st to June 30th of the following year. This approach is selected because on this website we often focus on regions with climates colder than those found in The Netherlands or Germany. In those colder climates, Hellmann points may typically start accruing well before November and continue until well after March.

Classification of winter severity

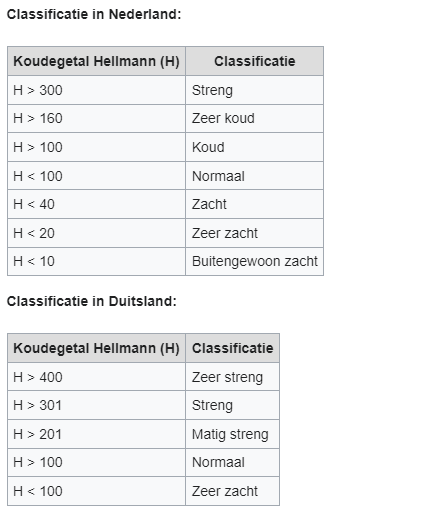

In the Netherlands and Germany the Hellmann number is used to classify the severity of a given winter. Classifications go from very mild to very severe in Germany and exceptionally mild to severe in the Netherlands, based on the number of Hellmann points. See the classifcations used in the Netherlands and Germany below.

Tables from Wikipedia. Streng = Severe, koud = cold, zacht = mild, zeer=very and buitengewoon = exceptionally.

Similar to how the classifications in The Netherlands and Germany vary, the interpretation of the Hellmann number should be put into context for the climate of other regions. For example, a winter with 350 Hellmann points will not be considered severe in Lapland.

Dis(advantages) of using the Hellmann number

Utilizing the Hellmann method to classify winter severity has the advantage of capturing the intensity of cold periods without allowing them to be offset by warmer intervals. Simultaneously, this can sketch an unnuanced picture of the winter, as a few very cold days can yield a high Hellmann number, while the winter can be mild overall. In regions with a rather mild climate, using the Hellmann metric can potentially lead to underestimating winters with significant night-time frost but temperatures that rise above freezing during the day.

Other metrics one could look at to assess winter severity include the average winter temperatures, frost days, ice days and other, similar variables.

Trends in Hellmann number in The Netherlands

To get a better intuition for the Hellmann number – and simultaneously learn something about the Dutch climate – let’s have a look at the statistics and trends of the Hellmann number in the country in which this cold index is most used: the Netherlands.

The current climatological Hellmann number in the Netherlands is 43.9 (based on 1991-2020 climate). This is down from 57.3 between 1981-2010 – a decline of 23%. The highest Hellmann score ever recorded the Netherland’s main weather station in De Bilt is 348.3 in 1947.

In total, 3 winters reached over 300 Hellmann points (1947, 1963, 1942), leading to the classification of ‘severe’. Simultaneously, since the start of the measurements, only 9 winters were classified as very cold (Hellmann number >160). The winter of 2014 was the first winter with a Hellmann number of 0.0, not accruing any Hellmann points whatsoever, followed by 2020 with a mere 0.1 point.

The trends are clear: Hellmann numbers are on the decline. In this century, no winter has reached a Hellmann number of 100, meaning that according to KNMI’s standards, none of the winters this century has reached the classification of ‘cold’. Additionally, the large majority of winters were classified as mild or very mild. The Hellmann threshold for cold winters already seemed relatively strict in the Netherlands even in the past century, but the lack of cold winters have sparked the debate if the Hellmann norms should be adjusted to the new climate.